Couples Therapy is Not a Fireproof Safe

Let’s start with a scenario. You’re a well-intentioned therapist, sitting across from a couple who claims they “just have communication issues.” The tension is thick, the air static with unspoken grievances. One partner—let’s call them Alex—keeps their gaze down, shoulders tight, barely speaking. The other—Jordan—takes the lead, talking over Alex, “explaining” their relationship problems with the confidence of a TED Talk speaker.

Now, maybe your gut nudges you. Something feels… off. But you push forward, believing in the transformative power of therapy. You hand them “I statements,” teach active listening, and help them “really hear each other.” Jordan nods enthusiastically. Alex offers a small, nervous smile. Progress, right?

Except, when they leave your office, Jordan’s grip tightens on Alex’s wrist.

“You made me look bad in there.”

And just like that, your therapy room—the space you thought was safe—has become another battleground.

This is why couples therapy and intimate partner violence (IPV) don’t mix. It’s like handing a lit match to someone sitting in a room full of gasoline and hoping the flames lead to warmth, not an explosion.

Why Is This Still a Debate?

Despite clear evidence that couples therapy is contraindicated in cases of IPV, many therapists still engage in it—sometimes unknowingly, sometimes out of a misguided belief that “every relationship deserves a chance.”

The problem? Therapy assumes equal footing. It’s built on the idea that both partners can show up, be vulnerable, and work toward change together.

But in abusive relationships, vulnerability is a weapon, not a shared experience. Power imbalances aren’t just present—they are the relationship. Asking a survivor to “express their needs” when those needs have been systematically ignored, belittled, or punished is not just unhelpful—it’s dangerous.

Yet, the field of psychotherapy has a complicated history with IPV. Some theoretical orientations have been crystal clear in their stance against couples therapy for abusive relationships. Others… well, let’s just say they’ve been a little too optimistic about human nature.

In This Post, We’re Going to Break It All Down:

• Why couples therapy can make IPV worse, not better

• How individual therapy (if done incorrectly) can also be harmful

• When “couples” therapy is contraindicated but individual therapy may be the solution

• What various theoretical orientations say about IPV

• How to recognize covert IPV in session

• What to do if IPV is disclosed mid-treatment

• How to work with survivors who minimize the abuse

• Why individual therapy for abusers requires an entirely different approach

• Knowing when to refer out within individual therapy (e.g., when more specialized services are needed, therapist safety is at risk, or the case exceeds your scope)

• Ethical and legal responsibilities for therapists

Throughout, I’ll sprinkle in therapist reflections (for when your gut starts whispering, “Am I handling this the right way?”), scripts (because we all know those moments when our brain glitches mid-session), and some metaphors to drive home why treating IPV like just another “relationship challenge” is akin to pouring water on a grease fire.

So, where do we start? With the very real ways that couples therapy doesn’t just fail IPV survivors—it actively puts them at greater risk.

Why Couples Therapy Makes IPV Worse, Not Better

Therapists love to believe in transformation. We sit in rooms with people at their lowest, and we witness growth, resilience, and healing. It’s kind of our whole thing. So it makes sense that when a couple walks into our office—one partner guarded, the other speaking for both—we might think, Maybe therapy can help them communicate better. Maybe if they just learn to understand each other, things will change.

But here’s the thing: Couples therapy isn’t a relationship rehab program for abusers. It’s a collaborative process built on the assumption that both partners are safe enough to be vulnerable. And when IPV is in the mix, that assumption shatters.

If we’re honest, we know this deep down. Still, many therapists proceed with couples work in IPV cases, either because they don’t recognize the abuse or because they believe therapy can somehow neutralize power imbalances. But research—and survivor testimony—tells a different story.

The “Communication Fix” Myth

At some point in training, most therapists heard this golden rule: Better communication leads to better relationships. It’s practically a therapy bumper sticker. But in abusive relationships, communication is not the issue—power and control are.

Let’s say we teach a survivor to confidently use “I statements” to express their needs:

• “I feel unheard when you don’t include me in decisions.”

• “I need to feel safe in our conversations.”

Sounds great, right? Healthy, assertive, and direct?

Except the moment the couple gets home, the abuser turns it into ammunition:

• “Oh, you ‘feel unheard’? Maybe if you weren’t so sensitive, we wouldn’t have this problem.”

• “You ‘need to feel safe’? That’s rich coming from someone who drives me to the edge with their drama.”

In a non-abusive relationship, these statements might lead to productive dialogue. In an abusive relationship, they become new angles for control and manipulation. Teaching a survivor better communication in therapy is like giving them a sharper sword without realizing their partner is the one holding the blade.

💬 Therapist Reflection: Am I mistaking a communication breakdown for an abuse dynamic?

Therapy as an Abuser’s Playground

If you’ve ever worked with a client who’s a skilled manipulator, you know how quickly therapy can be hijacked. In IPV cases, abusers don’t just “attend therapy”—they weaponize it.

Here’s how it plays out:

• Playing the victim – The abuser paints themselves as misunderstood, “just reacting” to their partner’s behavior.

• Gaining therapist validation – They latch onto neutral therapist language (“we both need to take responsibility”) and twist it to justify their actions.

• Using therapy as surveillance – They track what their partner says in session and punish them for it later.

• Love-bombing the therapist – They charm, perform insight, and convince the therapist that things aren’t that bad.

If an abuser can control a relationship outside of therapy, why wouldn’t they try to control it inside the therapy room too? The moment a therapist offers any neutral ground, the abuser claims it as their own.

💬 Therapist Reflection: Am I unconsciously giving an abuser more tools to manipulate their partner?

Escalation After Sessions

Here’s the ugly truth: Couples therapy doesn’t just fail survivors—it can actively endanger them.

Therapy encourages emotional expression. It invites honesty. But for survivors of IPV, honesty isn’t healing—it’s a risk. If a survivor shares their struggles in session, their abuser may:

• Retaliate after the session (“You embarrassed me in front of the therapist.”)

• Use therapy as proof that they’re the ‘real’ victim (“See? Even the therapist said we BOTH have work to do.”)

• Convince the survivor therapy isn’t helping (“They don’t understand us. We should stop going.”)

Even if a therapist privately suspects abuse, they can’t always act on it. IPV survivors often minimize or deny the abuse, fearing consequences. And abusers are rarely willing to admit to it—at least, not in a way that acknowledges responsibility. This means therapy keeps going while the survivor keeps suffering.

💬 Therapist Reflection: Is my therapeutic process unintentionally putting a survivor at greater risk?

🎭 Therapist Script: What to Say When You Suspect IPV in a Couple’s Session

If you start to notice signs of control, fear, or subtle coercion in session, pause before assuming this is just a “high-conflict couple.” Your response matters. Here’s one way to shift gears:

Therapist: “I want to check in for a moment. Sometimes in relationships, there are patterns where one partner feels unable to safely express themselves, even in therapy. I want to make sure that, in this space, both of you feel safe enough to be honest. Would you say that’s true for you?”

🔹 If the survivor looks hesitant or uncomfortable:

You can follow up gently with—

Therapist: “It’s okay if you don’t feel comfortable answering that here. If either of you ever wants to meet with me individually, I’m happy to set up a time.”

🔹 If the abuser jumps in to answer for their partner:

This is a red flag. Instead of pressing, observe their response and take note of how they frame the dynamic.

🔹 If the survivor reaches out later for individual therapy:

This gives you the opportunity to screen for IPV privately and offer support in a way that doesn’t increase their risk.

The Bottom Line

Couples therapy works when both partners can be vulnerable. But when power and fear drive the relationship, therapy doesn’t fix the problem—it feeds it.

For therapists, the real work isn’t trying to “mediate” an abusive relationship—it’s recognizing when couples therapy is the wrong tool for the job. The next step? Understanding how individual therapy (if done correctly) can offer a better alternative.

When “Couples” Therapy is Contraindicated, But Individual Therapy May Be the Solution

So, couples therapy is a no-go when IPV is involved. But does that mean therapy is off the table entirely? Not necessarily. Individual therapy can be a lifeline for survivors—when done correctly. It can also be useful for abusers, but only under very specific conditions.

This is where many therapists get stuck. If I can’t work with them as a couple, what do I do? The answer depends on who’s sitting in front of you—and what they’re hoping therapy will achieve.

When to Offer Individual Therapy to Survivors

For survivors, individual therapy can provide:

✅ A safe, confidential space to process what’s happening.

✅ Education about abuse dynamics (because many don’t realize they’re in an abusive relationship).

✅ Safety planning to reduce risk if they choose to leave.

✅ Support in healing self-blame and trauma responses.

Sounds straightforward, right? Not so fast. Survivors may not always be aware—or ready to acknowledge—that what they’re experiencing is abuse. They might come to therapy saying:

• “We just fight a lot, and I want to learn how to communicate better.”

• “My partner gets angry, but they’re under a lot of stress.”

• “I know I provoke them sometimes, so I want to work on myself.”

Therapists need to balance meeting the client where they are while gently helping them recognize abusive patterns—without pushing too hard, too soon.

🎭 Therapist Script: Helping Survivors Recognize Abuse Without Labeling It Prematurely

🔹 Client: “I think if I could just be less reactive, things wouldn’t escalate so much.”

🔹 Therapist: “It sounds like you’re carrying a lot of responsibility for how conflict plays out in your relationship. Can I ask—when these escalations happen, do you feel like your partner also takes responsibility for their actions?”

✅ Why this works: Instead of jumping in with “That sounds like abuse” (which may shut the client down), this encourages reflection and self-trust—key ingredients for breaking free from coercion.

🔹 Client: “They say they do, but then they tell me it wouldn’t happen if I just listened to them better.”

🔹 Therapist: “That’s really hard. It sounds like they put a lot of weight on you to control their reactions. How does that feel for you?”

✅ Why this works: It validates the client’s experience while inviting them to question the imbalance.

When NOT to Offer Individual Therapy to Survivors

There are times when individual therapy might not be the best fit—or might even increase danger.

🚫 If the abuser controls their access to therapy. If a survivor can only attend therapy with their partner’s permission (or under their watchful eye), they may not be able to speak freely. In these cases, connecting them with domestic violence services may be a better option.

🚫 If therapy becomes a trap. Some abusers “allow” their partners to go to therapy as long as it doesn’t challenge the relationship. If a survivor starts to gain confidence or question things, the abuser might force them to quit therapy. If this is happening, work on safety planning and provide resources they can access later if needed.

🚫 If the survivor is in immediate danger. If a client discloses physical threats, stalking, or escalation, therapy alone isn’t enough. This is a crisis intervention situation. Connect them to resources that prioritize safety first.

Can Abusers Get Individual Therapy? Yes—But With Major Caveats.

Survivors aren’t the only ones who seek therapy. Some abusers also walk into our offices, often saying things like:

• “I have anger issues, and I don’t want to take it out on my partner.”

• “I was raised in a violent household, and I don’t want to repeat that cycle.”

• “I need help controlling my emotions.”

This can feel like progress. But here’s the hard truth: Therapists can’t ‘fix’ an abuser just because they show up to therapy. Many abusers use therapy to:

🚩 Seek validation instead of accountability. (“I’m the real victim here.”)

🚩 Learn how to manipulate more effectively. (“Now I have the language to sound remorseful.”)

🚩 Prove to their partner they’re “working on it” to keep them from leaving.

That doesn’t mean abusers can’t change—but it does mean therapy has to be structured in a way that prevents manipulation and ensures actual accountability.

🎭 Therapist Script: Setting Boundaries With an Abusive Client

🔹 Client: “I just need help controlling my anger so my partner doesn’t set me off.”

🔹 Therapist: “I want to be clear—our work won’t focus on managing anger in the moment as much as it will focus on accountability for your choices. We won’t work on controlling reactions. We’ll work on changing patterns that harm your partner. If that’s something you’re open to, we can continue. If not, I can help you find a different resource.”

✅ Why this works: It sets the expectation upfront that therapy isn’t about managing outbursts—it’s about dismantling abusive behaviors.

When to Refer Out Instead of Taking On an Abusive Client

Therapists should consider referring out if:

🚫 The client is seeking therapy as a way to “prove” they’re changing but shows no real effort.

🚫 They deflect blame and refuse accountability.

🚫 They’re still engaging in active harm toward their partner.

🚫 You don’t have specific training in working with perpetrators of IPV.

In these cases, Batterer Intervention Programs (BIPs) are often a more appropriate option than traditional therapy. These programs focus on accountability, group dynamics, and structured interventions that prevent manipulation.

The Bottom Line

Therapy isn’t a one-size-fits-all intervention for IPV. When couples therapy is off the table, individual therapy can be a powerful alternative—but only when done thoughtfully.

✅ For survivors, therapy can be a path to safety, healing, and self-trust.

❌ For abusers, therapy should never be about “relationship repair”—it has to be about owning harm and changing behaviors.

If therapists aren’t careful, individual therapy can become another tool for control instead of a path to healing. The next step? Understanding the stances of different theoretical orientations on IPV—because not all therapy models approach this issue the same way.

What Various Theoretical Orientations Say About IPV

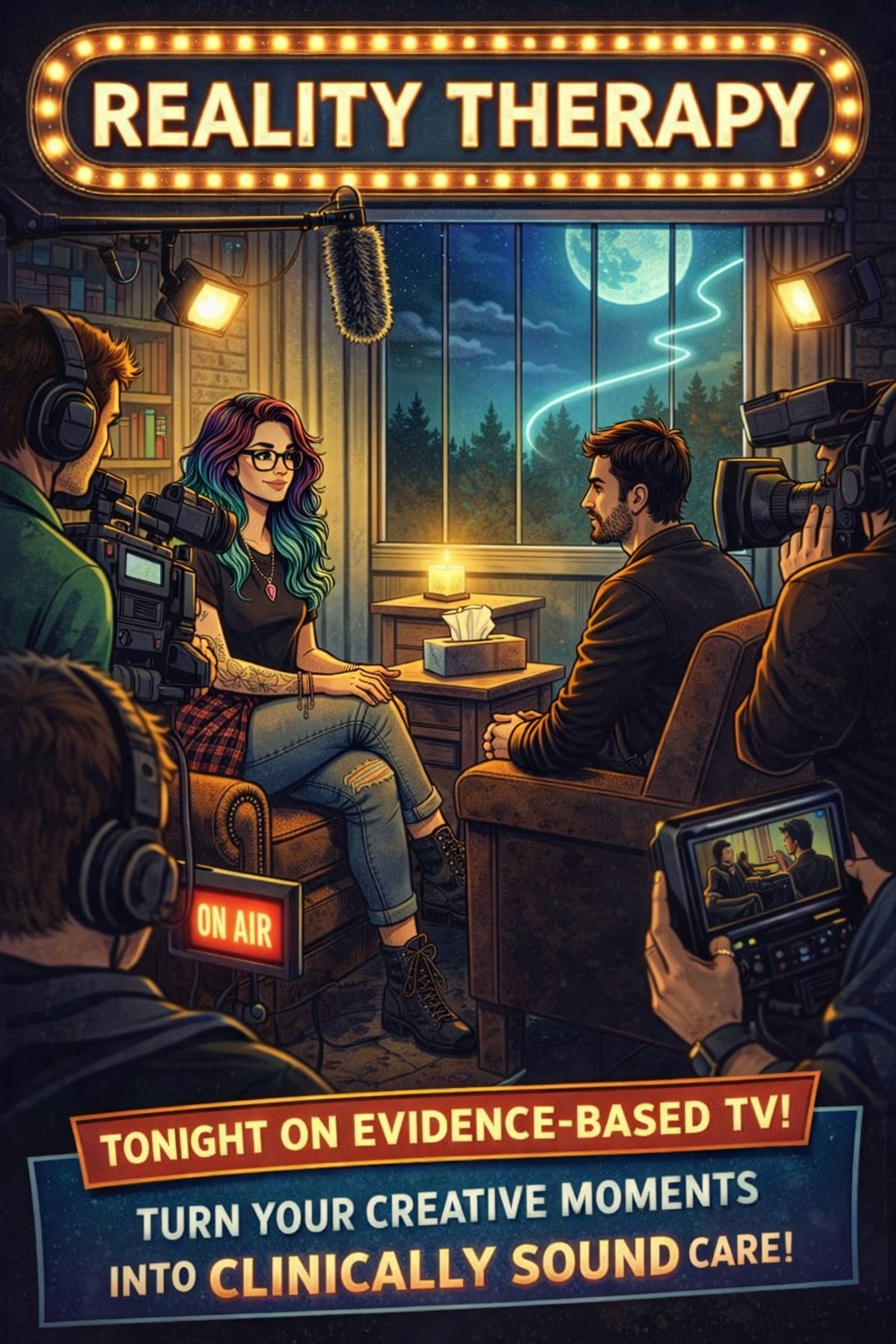

Therapists love a good theoretical framework. It’s how we make sense of human behavior, guide interventions, and (let’s be real) justify our existence when people ask why they should pay us to talk about their feelings.

But not all therapy models are created equal when it comes to intimate partner violence. Some explicitly reject couples therapy in IPV cases. Others have had to adjust over time after realizing that their approaches—when applied to abuse—were about as useful as handing someone an umbrella during a hurricane.

So let’s break down where major orientations stand on IPV, the good, the bad, and the misguided optimism.

Trauma-Informed Therapy: The Gold Standard for IPV Work

If there’s one approach that gets it right when it comes to IPV, it’s trauma-informed therapy. This framework recognizes:

✅ Safety first. Healing is impossible when a person is still in danger.

✅ Empowerment over pressure. Survivors decide when and how they want to engage in therapy.

✅ No forced reconciliation. The goal is not to “fix the relationship” but to support the survivor in finding clarity and safety.

🎭 Therapist Reflection: Am I prioritizing my client’s safety over my desire to help “repair” their relationship?

🔹 Where it shines: Trauma-informed therapy puts the survivor in control. It respects the complexity of leaving an abusive relationship, acknowledging that survivors don’t just need validation—they need a plan.

🔹 Where it stops short: While it focuses on survivors, trauma-informed therapy doesn’t inherently include strategies for working with perpetrators, which is a separate skillset.

Attachment Theory: Helpful, But Also a Trap

Attachment theory has made a massive resurgence in modern therapy. And sure, understanding attachment wounds can help many clients navigate relationships.

But here’s where it goes sideways in IPV work: Therapists sometimes frame abuse as an “attachment injury” rather than what it is—an exertion of power and control.

👀 Red flags to watch for:

🚩 Calling IPV a “pursuer-distancer” dynamic. (No, it’s not just anxious and avoidant attachment styles clashing. It’s abuse.)

🚩 Focusing too much on “repairing the bond” instead of addressing safety first.

🚩 Treating IPV as a “miscommunication” instead of a systemic pattern of harm.

🔹 Where it shines: Attachment-based work can be very useful for survivors after they’re out of the relationship to heal trust issues and relational wounds.

🔹 Where it fails: Some therapists mistakenly try to “strengthen the bond” between the survivor and their abuser, which is a recipe for disaster.

🎭 Therapist Reflection: Am I treating IPV like an attachment issue when it’s actually about power and control?

Gottman Method: Excellent for Relationships—Not for IPV

Gottman Method is one of the most research-backed approaches to couples therapy. But even John Gottman himself has been very clear:

🚨 “We do not do couples therapy when there is ongoing domestic violence.” 🚨

The Gottman Method is based on:

• Mutual emotional bids (impossible in an abusive relationship).

• Conflict de-escalation (useless when one partner uses escalation as a control tactic).

• Both partners engaging in repair attempts (abusers rarely repair—unless it benefits them).

🎭 Therapist Reflection: Am I applying relationship tools in a situation where the real issue is harm and fear?

🔹 Where it shines: The Gottman Method is great for healthy couples struggling with conflict.

🔹 Where it fails: It assumes both partners want to improve the relationship and have the capacity to do so—assumptions that collapse in IPV cases.

Emotionally Focused Therapy (EFT): Powerful, But Risky in IPV

EFT is all about deepening emotional bonds. But here’s the problem:

🤔 Should we be helping an abuser create a “deeper emotional bond” with their partner?

Therapists using EFT sometimes fall into the trap of framing IPV as an emotional disconnection problem. This leads to misguided interventions, like:

🚩 Encouraging a survivor to “express their core emotions” to their abuser.

🚩 Helping an abuser “connect with their vulnerability” rather than take responsibility.

🚩 Focusing on the couple’s emotional cycle instead of the survivor’s safety.

🔹 Where it shines: EFT can help survivors heal after leaving an abusive relationship, particularly in understanding their attachment patterns post-trauma.

🔹 Where it fails: It can inadvertently reaffirm an abuser’s emotional control over their partner.

🎭 Therapist Reflection: Am I mistaking manipulation for emotional disconnection?

CBT & DBT: Good for Survivors, Useless for Abusers

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) and Dialectical Behavior Therapy (DBT) are excellent for survivors because they:

✅ Help reframe self-blame.

✅ Reduce trauma responses.

✅ Teach emotion regulation (for survivors struggling with PTSD symptoms).

But for abusers? 🚨 Not a good standalone approach. 🚨

CBT and DBT focus on changing thoughts and behaviors, but IPV isn’t just about bad thinking patterns or poor emotion regulation. It’s about power and control.

🎭 Therapist Reflection: Am I assuming an abuser’s problem is “emotional dysregulation” when it’s actually entitlement and coercion?

Psychoanalysis & Depth Psychology: Sometimes Insight Is Useless

Ah, psychoanalysis—the granddaddy of therapy models. Depth work can be fantastic for survivors who need to:

✅ Process unconscious beliefs about relationships.

✅ Explore intergenerational trauma.

✅ Rewrite internalized narratives about love and safety.

But for abusers? A dangerous game. Some might love spending years analyzing their childhood while continuing to terrorize their partner at home.

🔹 Where it shines: Survivors can use depth work to reclaim their personal narrative.

🔹 Where it fails: Abusers don’t need “deeper self-awareness.” They need accountability.

🎭 Therapist Reflection: Am I mistaking self-awareness for actual change?

Narrative Therapy: Powerful for Survivors, Risky for Abusers

Where to place: After Psychoanalysis & Depth Psychology

🔹 Where it shines: Narrative therapy helps survivors reframe their story, separate themselves from blame, and reclaim agency.

🔹 Where it fails: If applied incorrectly, it can let abusers externalize their choices (“The problem isn’t me, it’s ‘Anger’”) rather than taking responsibility.

🔹 Therapist Reflection: Am I helping a survivor rewrite their story, or am I allowing an abuser to rewrite theirs in a way that avoids accountability?

Internal Family Systems (IFS): Helpful for Survivors, Dangerous for Abusers

Where to place: After CBT & DBT

🔹 Where it shines: IFS can help survivors recognize protective parts (like fawning or dissociation) and create internal safety.

🔹 Where it fails: Abusers may use “parts work” to deflect blame (“It wasn’t ‘me,’ it was my wounded inner child”).

🔹 Therapist Reflection: Am I helping a survivor integrate protective parts, or am I giving an abuser a way to avoid accountability?

Somatic Therapy: Great for Survivors, Not for Abuser Rehabilitation

Where to place: After Trauma-Informed Therapy

🔹 Where it shines: Survivors often hold trauma in the body, and somatic therapy helps release stored fear and dysregulation.

🔹 Where it fails: While useful for trauma healing, it does nothing to address power and control dynamics in an abuser.

🔹 Therapist Reflection: Am I helping a survivor feel safe in their body, or am I offering an abuser a way to “regulate” without changing harmful behaviors?

Existential Therapy: Useful for Survivors, Over-Intellectualized for Abusers

Where to place: Before Psychoanalysis & Depth Psychology

🔹 Where it shines: Existential therapy helps survivors navigate freedom, meaning, and reclaiming autonomy after abuse.

🔹 Where it fails: Abusers might intellectualize their actions, shifting the conversation to meaning and suffering rather than consequences.

🔹 Therapist Reflection: Am I helping a survivor reclaim their autonomy, or am I allowing an abuser to philosophize their way out of accountability?

Feminist Therapy: One of the Best for IPV Cases

Where to place: After Trauma-Informed Therapy

🔹 Where it shines: Feminist therapy directly addresses power imbalances, systemic oppression, and the intersectionality of IPV.

🔹 Where it fails: Rarely—but some therapists over-focus on social causes and miss personal accountability in abusers.

🔹 Therapist Reflection: Am I helping my client recognize systemic oppression while also addressing their personal choices?

The Bottom Line

Not all therapy models translate well to IPV. The key takeaway?

✅ Survivors need therapy that prioritizes safety, empowerment, and trauma recovery.

❌ Abusers need structured accountability—not insight, vulnerability work, or relationship skills.

As therapists, our job isn’t to apply a model blindly—it’s to recognize when a framework is ineffective or, worse, dangerous.

How to Recognize Covert IPV in Session

Not all abuse looks like bruises and screaming matches. Some of the most insidious forms of intimate partner violence happen in the shadows—woven into the fabric of everyday interactions in ways that are so subtle, so socially normalized, that even therapists can miss them.

Covert IPV isn’t about explosive fights; it’s about eroding someone’s autonomy, sense of reality, and ability to make choices without fear. And when these patterns show up in therapy, they don’t always announce themselves. Instead, they slip in through the cracks—hidden under “relationship struggles,” “miscommunication issues,” and partners who seem just charming enough to make you second-guess your gut.

So how do we spot it? Here’s what to look for.

Who Controls the Narrative?

In therapy, who is doing the storytelling? If one partner dominates the conversation, speaks for the other, or subtly (or not-so-subtly) shapes the therapist’s perception of the relationship, that’s a red flag.

🚩 Signs of Narrative Control:

• One partner frequently interrupts or “corrects” the other’s version of events.

• The survivor defers to their partner when asked a direct question.

• The abuser is exceptionally charming—making sure the therapist sees them as the reasonable one.

• The therapist gets a vague sense that “something feels off” but struggles to put a finger on it.

🎭 Therapist Reflection: Am I hearing both partners equally, or is one person filtering all the information?

The Art of Minimization and Deflection

Abusers rarely walk into therapy and announce, “I’m controlling and emotionally abusive.” Instead, they reframe their behaviors to downplay harm and shift blame.

🚩 Common Minimization Tactics:

• Joking about harmful behaviors. (“Yeah, sometimes I get a little intense, but you know me—I’m just passionate.”)

• Framing control as care. (“I just want to make sure they’re safe. That’s why I check their phone sometimes.”)

• Blaming their partner’s “sensitivity.” (“They take everything so personally—I can’t say anything without it being a big deal.”)

• Framing therapy as “fixing” their partner. (“If they could just learn to manage their anxiety better, we wouldn’t have these issues.”)

🔥 Pro tip: If one partner starts a sentence with “It’s not like I…” or “I wouldn’t say I’m controlling, but…”—there’s a good chance they’re about to minimize something very concerning.

🎭 Therapist Reflection: Am I allowing an abuser to frame their actions in a way that downplays harm?

Fear Disguised as Compromise

Survivors often don’t realize they’re acting out of fear. Instead, their behaviors look like compromise, flexibility, or even self-blame.

🚩 Signs Fear is Present:

• The survivor quickly backtracks when expressing dissatisfaction.

• They laugh off hurtful comments made by their partner.

• They phrase things in a way that protects their partner’s feelings more than their own.

• They say things like “I just need to be more patient” or “I know I can be difficult.”

If a therapist misreads these cues, they might encourage more compromise—reinforcing a cycle where the survivor continues to suppress their own needs to keep the peace.

🎭 Therapist Reflection: Am I mistaking fear-driven appeasement for mutual compromise?

The Power of Nonverbal Cues

Sometimes, the truth of a relationship is in what isn’t said. Survivors may not voice their discomfort, but their bodies will.

🚩 Nonverbal Indicators of IPV:

• Flinching or tensing when their partner gestures or moves.

• Looking at their partner before answering.

• Avoiding eye contact with the therapist.

• Shrinking posture—crossed arms, hunched shoulders, physically making themselves smaller.

🔥 Pro tip: If you notice these cues but aren’t sure what they mean, try shifting your focus. Make direct eye contact with the survivor when asking a question. If they hesitate, shift uncomfortably, or glance at their partner before answering, there’s something deeper happening.

🎭 Therapist Reflection: Am I paying attention to body language, or am I only listening to words?

The Sudden Personality Shift

🚩 One of the biggest tells? A survivor’s entire energy shifts the moment their partner is out of the room.

• They seem lighter, more expressive, more relaxed.

• Their tone shifts from careful to candid.

• They speak more freely—but the moment their partner returns, the shift reverses.

🔥 Pro tip: Pay attention to what happens in the first 30 seconds after one partner leaves the room. That’s often when the survivor’s real feelings surface.

🎭 Therapist Reflection: Does my client seem like two different people depending on whether their partner is present?

🎭 Therapist Script: What to Say When You Suspect Covert IPV

If something feels off, but you don’t have a direct disclosure, gently test the waters.

🔹 Therapist (during a moment of hesitation):

“You seem like you’re being really thoughtful about how you answer. I just want you to know—this space is for you. You don’t have to filter what you say here.”

🔹 Therapist (if the survivor backtracks a statement):

“I noticed you just walked back what you said. I want to check in—did you mean what you originally said, or are you feeling unsure about sharing it?”

🔹 Therapist (if you notice them looking at their partner before answering):

“I see you looking toward your partner before you answer. That makes me curious—do you feel comfortable sharing openly in this space?”

🚨 If at any point you suspect IPV, offer the survivor an individual session.** That can be a turning point in whether or not they feel safe enough to disclose what’s really happening.**

The Bottom Line

IPV isn’t always obvious. It hides behind charming abusers, self-doubting survivors, and cultural narratives that tell us “all couples have issues.”

But therapists aren’t just here to help people communicate better—we’re here to recognize when communication isn’t the issue. Power, control, and fear are.

If you sense something is wrong, trust that instinct. Survivors often don’t need a therapist to “fix” their relationship. They need someone to see them.

What to Do When IPV is Disclosed Mid-Treatment

So you’re in session, and then it happens.

A moment of hesitation. A long pause. And then, the words spill out—maybe in a whisper, maybe in a flood.

“Sometimes I feel scared when they get angry.”

“I don’t know if this is normal, but they don’t let me have any privacy.”

“They don’t hit me, but… it feels like I can’t do anything without them controlling it.”

You’ve been handed a fragile truth, and now your response matters more than ever. The way you handle this moment can either validate a survivor’s experience and empower them to take action—or shut them down and reinforce the fear that no one will believe them.

So what do you do next?

Step 1 – Regulate Your Own Reaction

Let’s be real—hearing an IPV disclosure in therapy can stir up a lot. You might feel:

• Shocked (especially if you didn’t suspect it).

• Angry (because you care about your client and hate that they’re being harmed).

• Overwhelmed (because suddenly the session’s stakes feel much higher).

• Righteous (because now you can help them see the truth).

Pause. Breathe. Regulate.

Survivors have often spent years managing other people’s reactions to their reality. If they sense you spiraling into panic, outrage, or urgency, they may shut down completely.

🔥 Pro tip: Your job in this moment is not to fix. It’s to be steady.

🎭 Therapist Reflection: Am I responding from a place of calm and curiosity, or am I reacting out of my own discomfort?

Step 2 – Validate, Don’t Investigate

Your client just took a massive risk by disclosing IPV. The worst thing you can do now? Interrogate them like a detective.

🚫 What NOT to say:

• “Are you sure it’s abuse?” (They already feel unsure. Don’t plant more doubt.)

• “Why haven’t you left?” (This assumes they can leave—a dangerous assumption.)

• “Have they ever hit you?” (Physical violence is not the only form of IPV.)

• “What did you do when that happened?” (This can sound like victim-blaming.)

✅ What TO say:

• “That sounds really painful. I’m so glad you told me.”

• “You don’t have to prove anything to me—I believe you.”

• “You deserve to feel safe, and what you’re describing doesn’t sound safe.”

🔥 Pro tip: Survivors are often testing the waters when they first disclose. Your response will determine if they open up further or shut down.

🎭 Therapist Reflection: Am I responding with validation, or am I accidentally making my client feel like they need to justify their experience?

Step 3 – Assess Immediate Safety Without Forcing Action

It’s tempting to jump into problem-solving mode when IPV is disclosed. But survivors aren’t projects to fix—they’re people who need support at their own pace.

🚩 Key questions to gently assess safety:

• “Do you feel safe at home right now?”

• “Are you worried about what will happen after this session?”

• “Has there ever been a time when you felt physically threatened or trapped?”

• “Do you have a place you can go if you ever needed space?”

🔥 Pro tip: DO NOT pressure a survivor to leave immediately. The most dangerous time in an abusive relationship is when the survivor tries to leave. If they aren’t ready, forcing the issue could put them in more danger.

🎭 Therapist Reflection: Am I prioritizing safety over my own desire for immediate action?

Step 4 – Offer Support Without Taking Over

Survivors have already had their autonomy stripped away by their partner. The last thing they need is another person telling them what to do. Instead of prescribing solutions, offer options and let them decide.

✅ Empowering ways to offer support:

• “Would it be helpful to explore some safety planning options?”

• “I have some resources I can share, if that feels okay for you.”

• “I’m here to support you in whatever next steps feel right for you.”

🚨 If safety is an immediate concern:

• If they disclose active threats, weapons, or immediate danger, you may need to explore emergency intervention (hotlines, shelters, or legal advocacy).

• If you’re a mandated reporter (varies by state & licensure), know your legal obligations.

• But if there’s no immediate risk, don’t pressure a report they aren’t ready for.

🔥 Pro tip: Survivors are more likely to seek help when they feel in control of the process.

🎭 Therapist Reflection: Am I respecting my client’s agency, or am I pushing them toward an outcome they may not be ready for?

🎭 Therapist Script: What to Say When IPV is Disclosed in Session

🔹 Client: “I don’t know if this counts as abuse, but…”

🔹 Therapist: “You don’t have to label it for it to be real. If you’re feeling unsafe, that’s what matters.”

🔹 Client: “It’s not that bad—I mean, other people have it worse.”

🔹 Therapist: “Comparing pain doesn’t make yours any less real. You deserve to feel safe.”

🔹 Client: “I don’t think I can leave.”

🔹 Therapist: “Leaving is one option, but not the only one. We can talk about what you want and what would make you feel safest.”

🔹 Client: “I shouldn’t have said anything.”

🔹 Therapist: “I know this is hard to talk about. I want you to know you don’t have to carry this alone.”

The Bottom Line

Hearing an IPV disclosure in session isn’t about fixing, saving, or rushing a survivor toward an outcome. It’s about holding steady, validating their experience, and helping them navigate next steps in a way that prioritizes their safety and agency.

Your role isn’t to be a rescuer. Your role is to be a witness, an anchor, and a safe place to land.

How to Work with Survivors Who Minimize the Abuse

Not every survivor walks into therapy ready to call what’s happening to them abuse. In fact, many will actively resist that label. They might tell you their partner “isn’t perfect,” that “all relationships have problems,” or that they just need to “handle things better.”

This isn’t denial in the way most people think of it. It’s a survival mechanism. If a person is living in a situation where they have limited control, limited options, and real risks associated with leaving, minimizing the abuse isn’t just psychological—it’s strategic.

So how do therapists honor this reality while gently guiding clients toward insight and safety?

Understanding Why Survivors Minimize

🚩 Common reasons survivors downplay abuse:

• Survival logic. (“If I admit it’s abuse, then I have to do something about it. And I’m not ready for that.”)

• Hope for change. (“They’re working on it. They’re going to therapy now.”)

• Love & trauma bonds. (“They’re not all bad. There are good times too.”)

• Fear of escalation. (“If I start calling it abuse, what happens if they find out?”)

• Cultural & societal messaging. (“It’s not abuse if they aren’t hitting me.”)

• Guilt & self-blame. (“Sometimes I make them mad. I should be more patient.”)

🔥 Pro tip: Survivors don’t need to be forced into recognizing abuse. They need space to reach their own conclusions—on their own timeline.

🎭 Therapist Reflection: Am I rushing my client toward a realization they aren’t ready for?

When NOT to Push the “Abuse” Label

Many therapists, upon recognizing IPV, feel an urgent need to name it. But that urgency often comes from our discomfort, not the client’s needs.

🚫 What NOT to say:

• “That’s abuse, plain and simple.” (If they aren’t ready to hear it, they’ll shut down.)

• “You need to get out.” (That assumes they can—and that it’s safe to do so.)

• “I can’t believe you put up with that.” (This sounds like judgment, even if unintended.)

• “They sound like a narcissist.” (Armchair diagnosing the partner isn’t helpful—it shifts focus off the client’s experience.)

✅ What TO say:

• “It sounds like you’re in a really painful situation.”

• “I hear that you love them, and I also hear that you’re feeling unsafe.”

• “It makes sense that you’d want to focus on the good parts of the relationship.”

• “What’s it like for you when things are at their worst?”

🔥 Pro tip: Instead of trying to convince a survivor that they’re in an abusive relationship, help them reflect on their lived experience.

🎭 Therapist Reflection: Am I honoring my client’s need for emotional safety, or am I prioritizing my need for clarity?

Gently Encouraging Cognitive Dissonance

One of the most effective ways to help a survivor recognize abuse without forcing the issue is to highlight contradictions in what they’re already saying.

🚩 Examples of gentle reality-testing:

🔹 Client: “They’re not abusive, they just lose control sometimes.”

🔹 Therapist: “That makes sense. And yet, do they ‘lose control’ with their boss? Their friends? Or just with you?”

🔹 Client: “They only act that way when they’re stressed.”

🔹 Therapist: “Stress is hard for a lot of people. What do you think makes the difference between someone who lashes out under stress and someone who doesn’t?”

🔹 Client: “They say they’re sorry afterward.”

🔹 Therapist: “What does ‘sorry’ mean in your relationship? Does it change their behavior, or is it just words?”

🔥 Pro tip: Survivors don’t need a therapist to tell them what’s happening. They need a therapist who helps them connect the dots for themselves.

🎭 Therapist Reflection: Am I allowing my client to process at their own pace, or am I rushing their insight?

When Survivors Blame Themselves

One of the hardest parts of working with survivors is hearing them say things like:

• “I shouldn’t have provoked them.”

• “I know how to avoid setting them off.”

• “I just need to be better at handling their moods.”

Survivors are experts in predicting and preventing harm. Many have spent years carefully adjusting their behavior to minimize explosions, de-escalate conflict, and keep themselves safe.

🚫 What NOT to say:

• “It’s not your fault.” (This is true, but it may not land if they deeply believe otherwise.)

• “You’re a victim.” (Some survivors hate that word and will reject the framing.)

• “You need to stop making excuses for them.” (This feels invalidating and harsh.)

✅ What TO say:

• “It sounds like you’ve learned a lot of ways to keep yourself safe.”

• “I hear how much work you put into managing their reactions. Have you ever noticed how little work they put into managing their own?”

• “What would it be like to be in a relationship where you didn’t have to do all this work to avoid setting someone off?”

🔥 Pro tip: Survivors often know deep down that the abuse isn’t their fault. But they may not feel safe fully accepting that yet.

🎭 Therapist Reflection: Am I giving my client space to unlearn self-blame at their own pace?

🎭 Therapist Script: What to Say When Survivors Minimize Abuse

🔹 Client: “It’s not like they hit me or anything.”

🔹 Therapist: “That makes sense. And at the same time, you’ve told me you don’t feel safe. Can we talk about what safety means to you?”

🔹 Client: “They don’t mean to hurt me.”

🔹 Therapist: “Intention matters, but so does impact. How does their behavior affect you?”

🔹 Client: “They’ve been better lately.”

🔹 Therapist: “That’s great to hear. How long does the ‘better’ usually last?”

🔹 Client: “I just need to be more patient.”

🔹 Therapist: “I hear that patience is important to you. Do you feel like they show the same patience toward you?”

🔥 Pro tip: Survivors need gentle reality-checking—not forceful confrontation.

The Bottom Line

Minimization isn’t ignorance or stubbornness. It’s often a deeply ingrained survival response.

As therapists, our role isn’t to push someone toward a realization before they’re ready—it’s to create a space where clarity can unfold safely.

If we rush the process, we risk losing their trust. If we let them lead, they’ll arrive at the truth in their own time.

Why Individual Therapy for Abusers Requires an Entirely Different Approach

So, we’ve established that couples therapy is a disaster for IPV cases and that individual therapy can be a lifeline for survivors—but what about the other side of the equation?

Many therapists, especially those trained in compassion-focused models, want to believe that abusers can change with the right insight, emotional support, or self-work.

And while change is possible, individual therapy alone is almost never enough.

Here’s why.

The Myth of the “Insight-Based Fix”

🚩 Many therapists assume that if an abuser can just “understand” the harm they cause, they’ll stop.

❌ Reality check: Abusers don’t harm their partners because they “don’t know better.” They harm them because it benefits them.

Common therapist traps:

• Focusing on childhood trauma instead of current harm (“They had a hard life; they don’t know any better.”).

• Teaching emotion regulation skills without addressing power and control dynamics (“Let’s help them manage anger so they don’t explode.”).

• Encouraging vulnerability without accountability (“If they just learn to express their feelings, they’ll stop being abusive.”).

🔥 Pro tip: Some abusers love therapy because it gives them new language to manipulate their partners more effectively. If therapy focuses too much on their pain, they may walk away feeling even more justified in their actions.

🎭 Therapist Reflection: Am I mistaking emotional awareness for actual change?

The Difference Between Shame and Accountability

🚩 Many abusers cry in therapy. Many talk about feeling worthless. That doesn’t mean they’re changing.

Therapists often confuse shame with accountability. But there’s a key difference:

Shame

Accountability

“I’m a horrible person.”

“I harmed my partner, and I need to stop.”

“I don’t deserve love.”

“My actions have real consequences.”

“I had a hard childhood.”

“That doesn’t justify hurting someone.”

“I feel so bad for what I did.”

“I am actively making changes so I don’t do it again.”

🔥 Pro tip: Therapists can unknowingly reinforce shame spirals by offering too much reassurance (“You’re not a bad person.”). Instead, shift the focus: “Feeling bad isn’t enough—what are you doing differently?”

🎭 Therapist Reflection: Am I helping my client sit with accountability, or am I soothing their discomfort?

Why Therapy Alone Doesn’t Work

🚩 Abusers need structured accountability, not just self-awareness.

This is why Batterer Intervention Programs (BIPs) exist. Unlike traditional therapy, these programs:

✅ Hold abusers accountable.

✅ Challenge justifications for violence.

✅ Teach non-coercive relationship skills.

✅ Involve group work, where other participants call out manipulation tactics.

🔥 Pro tip: Many abusers prefer individual therapy because it’s private, personalized, and easier to manipulate. Group settings disrupt that control.

🎭 Therapist Reflection: Am I offering individual therapy when a structured intervention would be more effective?

When (and How) to Work with Abusive Clients

🚩 There are times when individual therapy is appropriate—but only under strict conditions.

🔹 When the client has already completed (or is actively in) a BIP.

🔹 When the work focuses on accountability, not victimhood.

🔹 When the therapist is trained in IPV dynamics and abuser intervention.

🔹 When the therapist maintains strict ethical boundaries (e.g., no couples therapy alongside individual work).

🚫 When NOT to take on an abusive client:

• If they want therapy to get their partner back.

• If they refuse to take full responsibility.

• If they expect therapy to focus on their pain instead of their harm.

🔥 Pro tip: Before agreeing to work with an abusive client, ask: “Am I the right person for this, or is there a better intervention available?”

🎭 Therapist Reflection: Am I engaging in therapy that actually reduces harm, or am I reinforcing false change?

🎭 Therapist Script: Setting Boundaries with an Abusive Client

🔹 Client: “I know I have issues, but my partner isn’t innocent either.”

🔹 Therapist: “Right now, my focus is on your actions. Your partner isn’t in this room—you are. What can you take responsibility for?”

🔹 Client: “I just need help managing my anger.”

🔹 Therapist: “Anger management and abuse intervention are different things. Are you open to working on how you use power and control in relationships?”

🔹 Client: “I don’t need a group, I just need one-on-one help.”

🔹 Therapist: “Individual work can be helpful, but it’s not a substitute for accountability work. Are you open to a structured program?”

🔥 Pro tip: If a client refuses accountability, therapy won’t help them change. Your best intervention may be a firm referral elsewhere.

The Bottom Line

Therapy isn’t a cure for abusive behavior. Accountability is.

✅ Survivors need safety, validation, and autonomy.

❌ Abusers need structured intervention, not insight-driven therapy.

If therapists aren’t careful, individual therapy can become another tool of manipulation—allowing abusers to reframe themselves as victims rather than active participants in harm.

The next step? Knowing when to refer out—because sometimes, the best therapy we can offer is knowing when NOT to engage.

Only After Accountability Can Therapy Be Used to Support Change

Therapists must not mistake therapy for accountability. Therapy can support change in those who have caused harm, but it is not the intervention that creates change. Batterer Intervention Programs (BIPs) exist for a reason: they hold abusive individuals systematically accountable in ways that therapy alone cannot.

If a therapist is working with a former perpetrator of IPV, therapy should only come into play after meaningful, sustained accountability has been demonstrated. Without this, therapy runs the risk of reinforcing manipulation, minimizing harm, or offering an unearned sense of progress.

The Pillars of Genuine Accountability:

An abusive individual is not ready for therapy until they have shown:

✅ Full Ownership of Their Actions

They take unequivocal responsibility for their past behavior—without blaming, justifying, or minimizing.

✅ Cessation of All Abusive Behaviors

Accountability is not an apology—it’s a sustained change in behavior over time. If harm is still happening, therapy is premature.

✅ Completion of a Batterer Intervention Program (BIP)

Structured programs are the gold standard in accountability-based change. Therapy cannot replace a BIP, but it can be an adjunctive tool after completion.

✅ Willingness to Engage in Repair—Without Expectation

They acknowledge the harm caused without demanding forgiveness, reconciliation, or validation from the survivor.

✅ Recognition That Therapy is for Personal Growth—Not a Relationship Tool

If therapy is being used to win back a partner, prove change, or get sympathy, it is not being used ethically.

Survivor-Centered Interventions: Safety Before Therapy 🔥

Not all survivors are in a position where therapy is their first or most pressing need. Before therapy can be useful, survivors may require external support systems that prioritize safety and structural change. This can include:

🔹 Domestic Violence Advocacy Services – Helping survivors navigate their options, build support networks, and assess risk.

🔹 Shelter & Housing Resources – Ensuring safe, confidential places for survivors who are at risk of escalation or harm.

🔹 Legal Protections – Access to restraining orders, custody protections, and legal aid for survivors navigating the court system.

🔹 Financial Assistance & Employment Support – Breaking economic dependency that may prevent survivors from leaving.

Why This Matters: Therapy is not always the first step—survivors often need external interventions to even be able to consider therapy. If a client is still in immediate danger, therapy should focus on harm reduction, safety planning, and connection to resources before deeper psychological work can begin.

🔥 Pro Tip: If a survivor expresses fear about leaving but lacks a safety net, your role isn’t to push them—it’s to connect them with practical supports that reduce their risk.

💬 Therapist Reflection: Am I prioritizing external safety before assuming therapy is the right next step?

A Glimpse Into Traditional and Healthy Couples Therapy

So, we’ve spent a lot of time talking about why couples therapy and IPV don’t mix—but what does healthy couples therapy actually look like?

Therapists need to understand the contrast so they can recognize when a relationship is fundamentally incompatible with couples therapy versus when it may benefit from traditional relational work.

Here’s the difference between unhealthy, unsafe couples therapy and the kind of therapy that actually fosters growth.

The Foundation of Traditional Couples Therapy

In non-abusive relationships, couples therapy assumes that:

✅ Both partners have equal power and autonomy.

✅ Both partners are willing to engage in self-reflection and accountability.

✅ The relationship dynamic is built on trust, not fear or control.

✅ Both partners are safe to express emotions without retaliation.

🚩 If these conditions aren’t met, couples therapy is not just ineffective—it’s dangerous.

Unhealthy vs. Healthy Couples Therapy Dynamics

Unhealthy & Unsafe Therapy

Healthy & Productive Therapy

🚩 One partner dominates the conversation.

✅ Both partners share space equally.

🚩 One partner defers, self-edits, or minimizes their emotions.

✅ Both partners can express emotions without fear of consequences.

🚩 One partner blames the other for all problems.

✅ Both partners take responsibility for their role in conflict.

🚩 The therapist focuses on relationship repair instead of individual safety.

✅ The therapist ensures the work is safe before deepening emotional connections.

🚩 The therapist feels tension, dread, or gut discomfort when engaging with the couple.

✅ The therapist observes a foundation of mutual respect, even in conflict.

🔥 Pro tip: If you have to convince yourself that the couple is “fine” for therapy, they probably aren’t.

🎭 Therapist Reflection: Am I seeing signs of mutual engagement, or am I witnessing a dynamic of control?

The Goals of Healthy Couples Therapy

When couples therapy is appropriate, the focus is on:

✅ Strengthening communication and emotional safety.

✅ Helping partners work through attachment wounds and relational patterns.

✅ Fostering empathy, collaboration, and mutual problem-solving.

✅ Supporting secure connections while respecting individuality.

Healthy couples therapy doesn’t just teach people to “communicate better”—it helps them build a relationship that is safe, balanced, and fulfilling for both partners.

🚩 Why this doesn’t work for IPV:

• Abusers don’t seek communication—they seek control.

• Survivors aren’t struggling with connection—they’re struggling with safety.

🔥 Pro tip: If the core issue in a relationship is power, control, or coercion, couples therapy cannot fix that—only individual work and accountability can.

🎭 Therapist Reflection: Am I assuming that a relationship issue is about communication, when it may actually be about coercion and control?

When Relationship Conflict Is NOT IPV

Not every relationship with high conflict or emotional distress is abusive. It’s important to recognize:

✅ Conflict is normal. Fighting, misunderstandings, and emotional distance happen in all relationships.

✅ Toxic dynamics don’t always mean IPV. Some couples have poor communication, attachment wounds, or emotional dysregulation—but that doesn’t mean abuse is present.

✅ People can struggle with emotional expression without being controlling. Anger issues, avoidance, and emotional shutdown are not the same as coercive control.

🚨 The Key Difference: In abusive relationships, the core issue is power and control. In non-abusive but high-conflict relationships, both partners still retain agency, safety, and the ability to change without fear.

🔥 Pro tip: If a client feels free to express their needs and emotions without fear of retaliation, they may be struggling with communication rather than IPV. If fear or control is present, that’s a different conversation.

🎭 Therapist Reflection: Am I recognizing the difference between relationship conflict and coercive control?

The Bottom Line

🚫 Couples therapy cannot repair relationships where control, coercion, or fear are present.

✅ But in non-abusive relationships, it can be a powerful tool for deepening trust, communication, and emotional safety.

Therapists must recognize the difference between:

• A struggling couple who needs support and

• A dangerous dynamic where couples therapy will cause harm.

If the core issue is communication or connection, couples therapy may help.

If the core issue is power, control, or coercion, couples therapy is NOT the answer.

🚨 Therapists who fail to recognize this risk retraumatizing survivors and reinforcing abusive patterns.

When Is It Okay to Work with IPV in Therapy?

While most IPV cases should NOT be treated with couples therapy, that doesn’t mean therapy is off the table entirely. There are situations where therapy can be appropriate for survivors—and even, in limited circumstances, for those who have perpetrated abuse.

Clarification on Couples Therapy & IPV

Couples therapy and intimate partner violence (IPV) do not mix. Period. If there is ongoing or recent IPV, joint sessions are not a safe or ethical approach, as they can reinforce power imbalances, endanger the survivor, and enable further harm.

That said, there are rare cases where couples therapy might be appropriate—but only after very specific conditions are met:

✅ The abusive partner has fully completed a structured accountability program (e.g., a certified batterer intervention program).

✅ There has been a sustained period of demonstrated accountability and behavioral change—not just surface-level compliance.

✅ The survivor is not in active fear and has full autonomy in decision-making about therapy.

✅ A highly trained IPV-informed therapist is conducting sessions with strict safety protocols in place.

Even in these cases, individual therapy remains the priority. Any step toward joint sessions must be cautiously considered and driven by the survivor’s needs, not a pressure to “fix” the relationship.

This distinction is critical because many therapists mistakenly believe couples therapy can “treat” IPV. In reality, it can reinforce harm unless the power dynamic has been fully addressed and accountability work has been completed.

But the bar is high. Here’s when it is clinically sound to proceed.

When It’s Safe to Work with Survivors in Therapy

Survivors can absolutely benefit from individual therapy—but only under the right conditions.

✅ It’s safe to proceed when:

• The survivor is physically and emotionally safe to engage in therapy.

• The survivor has autonomy over their therapy (i.e., they aren’t being pressured into it by their partner).

• The therapist is IPV-informed and can recognize manipulation/coercion.

• The focus is on empowerment, trauma recovery, and safety planning—not on “fixing” the relationship.

🚨 Red flags that signal therapy alone isn’t enough:

• The survivor is still living with an actively abusive partner with no safety plan.

• The abuser has access to the survivor’s therapy records, messages, or appointments.

• The survivor is showing severe trauma responses that require crisis intervention rather than traditional therapy.

🔥 Pro tip: If a survivor is still in an active IPV situation, therapy should focus on harm reduction and stabilization—not on processing deep trauma yet.

🎭 Therapist Reflection: Is this therapy truly empowering my client, or are they still under their abuser’s control?

When It’s Safe to Work with Abusive Clients in Therapy

Let’s be clear: Most abusers should not be in traditional therapy, because therapy can easily become a tool for manipulation rather than a path to change.

However, in specific cases, therapy may be appropriate if the following conditions are met:

✅ The abusive partner has demonstrated sustained accountability.

• They fully acknowledge their actions without justifying or blaming.

• They have completed (or are actively participating in) a Batterer Intervention Program (BIP).

• They have stopped all abusive behaviors and are no longer exerting control over their partner.

✅ The therapy focus is on personal change—not the relationship.

• The goal is not “winning back” their partner—it’s examining and dismantling their patterns of control.

• Therapy is structured, boundaries are firm, and sessions are not being used to emotionally offload.

🚨 Red flags that signal therapy will not be effective for an abuser:

• They still minimize, justify, or shift blame for their behavior.

• They say they want therapy to “prove” to their partner that they’ve changed.

• They refuse group-based accountability programs (BIPs) and only want private therapy.

• They are still in an active relationship with the survivor and showing signs of coercion.

🔥 Pro tip: If the abuser is unwilling to engage in formal intervention (such as a BIP), individual therapy alone is not the answer. It will likely reinforce, rather than challenge, their entitlement and power dynamics.

🎭 Therapist Reflection: Am I working with an abusive client in a way that actually disrupts harmful behaviors, or am I providing a space where they can further justify their actions?

When (and How) to Engage in Couples Therapy After IPV

🚩 99% of the time, couples therapy is NOT appropriate in IPV cases.

But in very rare, carefully structured circumstances, it may be considered—only if all of the following conditions are met:

✅ The abuse has fully stopped, with a significant period of separation or intervention.

✅ The abusive partner has completed an intensive Batterer Intervention Program (BIP) and demonstrated sustained change.

✅ The survivor has expressed a clear, independent desire for reconciliation—not one born of fear or obligation.

✅ A highly skilled, IPV-trained therapist is conducting therapy, with clear safety protocols in place.

✅ Both partners have engaged in individual therapy first to establish independent stability.

🚨 If these conditions aren’t met, couples therapy will likely retraumatize the survivor and reinforce power imbalances.

🔥 Pro tip: Even when these conditions are met, couples therapy should only happen under strict guidelines, with IPV-specialized clinicians, and with the survivor’s safety as the top priority.

🎭 Therapist Reflection: Am I considering couples therapy because it is truly safe and appropriate, or because I want to believe in a happy ending?

The Bottom Line

Therapy and IPV don’t mix unless the work is highly structured, safety-driven, and accountability-based.

✅ Survivors benefit from individual therapy—but only when they are safe and autonomous.

✅ Abusive partners may engage in therapy—but only after real, sustained accountability.

❌ Couples therapy is almost never appropriate—except in highly specific, post-intervention cases.

If therapists don’t hold strict boundaries around when therapy is appropriate, they risk causing more harm than good.

Knowing When to Refer Out Within Individual Therapy

Therapists are trained to help—which sometimes makes it hard to admit when we’re not the best person for the job. But when it comes to IPV, knowing when to refer out isn’t just good practice—it’s a matter of safety.

So how do you know when it’s time to step back and connect your client with a more specialized resource? Here’s where to draw the line.

When a Survivor Needs More Than Therapy Can Provide

🚩 Therapy is NOT a substitute for crisis intervention. Survivors often need legal, financial, medical, or shelter-based support before therapy can even begin to be useful.

Signs It’s Time to Refer a Survivor to Additional Support:

🔹 They are in immediate physical danger. (Active threats, stalking, weapons in the home.)

🔹 They want to leave but have no resources. (No access to money, housing, or legal protections.)

🔹 They are experiencing severe PTSD symptoms that require a higher level of care.

🔹 The abuser controls their access to therapy. (Survivors being forced to “fix themselves” in therapy.)

🔥 Pro tip: Instead of just handing them a list of resources, help them make the first connection. Survivors are often exhausted, overwhelmed, and afraid—if you can make that initial phone call with them, it increases the likelihood that they’ll follow through.

🎭 Therapist Reflection: Am I asking therapy to do the job of crisis intervention?

When an Abusive Client Needs a Structured Program

🚩 If a client is actively harming their partner, therapy alone is NOT enough.

Batterer Intervention Programs (BIPs) exist for a reason. These structured programs provide:

✅ Accountability from facilitators and peers.

✅ Education on power, control, and coercion.

✅ Monitoring to prevent therapy from becoming a tool for manipulation.

Signs It’s Time to Refer an Abusive Client to a BIP:

🔹 They justify or minimize their behavior.

🔹 They refuse to take full accountability.

🔹 They want therapy as a way to “win back” their partner.

🔹 They resist structured intervention and only want individual work.

🚨 Warning: Some abusers insist that they don’t “need” a group and would rather do therapy privately. This is often a red flag. Group settings are harder to manipulate, which is why they’re the gold standard for IPV intervention.

🔥 Pro tip: If an abusive client resists accountability-based treatment, your best clinical move is to end therapy and refer out.

🎭 Therapist Reflection: Am I engaging in therapy that actually reduces harm, or am I allowing therapy to be used as a tool for control?

When a Case Is Outside Your Scope

🚩 Not every therapist is trained to handle IPV—AND THAT’S OKAY.

If you’re realizing that this work is beyond your expertise, referring out isn’t a failure—it’s ethical practice.

Signs It’s Time to Refer Out Due to Scope:

🔹 You don’t have IPV-specific training.

🔹 You feel unsure about how to navigate disclosures safely.

🔹 You’re emotionally overwhelmed by the case.

🔹 You notice countertransference is clouding your judgment.

🔥 Pro tip: If you’re unsure whether a case is outside your scope, consult with an IPV expert before making a decision.

🎭 Therapist Reflection: Am I holding onto this case because I’m the best fit—or because I feel guilty letting it go?

🎭 Therapist Script: How to Refer Out Without Abandoning the Client

🔹 Client (Survivor): “I don’t know what to do. I feel trapped.”

🔹 Therapist: “I want to make sure you have the best support possible. Would you be open to me connecting you with an advocate who specializes in this?”

🔹 Client (Abuser): “I just need you to help me control my temper.”

🔹 Therapist: “Anger management and abuse intervention are two different things. I can refer you to a program that specializes in accountability-based change. Would you be open to that?”

🔹 Client (Survivor): “I don’t want to talk to anyone else.”

🔹 Therapist: “I hear that. And I want to respect your autonomy while also making sure you have options. I can give you a few resources, and you can decide what feels right for you.”

🔥 Pro tip: Survivors often feel abandoned when therapists refer them out. The key is to frame it as expanding their support system, not dropping them.

The Bottom Line

Referring out isn’t giving up—it’s making sure your client gets the right help.

✅ Survivors deserve comprehensive, safety-centered support.

❌ Abusers need structured intervention, not insight-driven therapy.

⚠️ Therapists must know their own limits and recognize when a case exceeds their scope.

If we’re serious about not causing harm, we have to recognize when our role isn’t to treat—but to connect our clients with those who can.

Ethical and Legal Responsibilities for Therapists

Therapists navigating IPV cases aren’t just making clinical decisions—they’re also making ethical and legal ones. And in a field where confidentiality is sacred, IPV presents a major dilemma: When do we break confidentiality for safety? When do we let a survivor lead their own process? Where does our legal duty start and end?

These aren’t just theoretical questions—they’re the kind that can change the course of someone’s life. Let’s break it down.

Confidentiality vs. Duty to Warn

🚩 The biggest misconception about IPV cases? That therapists are always mandated to report abuse in adult relationships.

Reality check: IPV does not automatically trigger mandated reporting laws for adults unless specific circumstances apply. However, therapists can break confidentiality under duty to warn/duty to protect laws if:

🔹 There is an imminent, serious threat of harm to the client or another identifiable person.

🔹 The client discloses intent to commit lethal violence.

🔹 Weapons or extreme coercion are involved.

🔥 Pro tip: If you’re unsure whether a disclosure meets the threshold for breaking confidentiality, consult your licensing board or legal counsel before making a move.

🎭 Therapist Reflection: Am I assuming I need to report, or am I carefully assessing legal and ethical obligations?

Mandatory Reporting for Special Cases

While IPV itself isn’t always reportable, here’s when it is:

🚨 If the IPV involves child abuse:

• If a child witnesses repeated violence in the home and is experiencing trauma symptoms.

• If a survivor is unable to provide basic care due to IPV-related distress.

🚨 If the IPV involves elder or dependent adult abuse:

• If an abusive partner is harming or coercing a vulnerable adult.

🚨 If the survivor is at immediate risk of homicide or extreme harm:

• Some jurisdictions allow (or require) therapists to intervene under duty to protect.

🔥 Pro tip: If you do have to report, always inform the client first, explain what will happen, and provide emotional support in that process.

🎭 Therapist Reflection: Am I distinguishing between cases where I am legally required to report and cases where confidentiality is critical for the client’s safety?

Working with Survivors Who Aren’t Ready to Leave

🚩 Ethically, therapists should never pressure a survivor to leave their partner.

❌ What NOT to say:

• “You have to leave. It’s the only way to be safe.”

• “You’re enabling the abuse by staying.”

• “You can’t heal while you’re still in the relationship.”

✅ What TO do instead:

• Help them assess risk factors. (“What’s your biggest concern if you decided to leave?”)

• Encourage harm reduction strategies. (“What are small ways you can create more safety for yourself right now?”)

• Support autonomy. (“You get to decide what’s best for you, and I’ll support you in that.”)

🔥 Pro tip: Leaving is the most dangerous time in an abusive relationship. If a survivor isn’t ready, therapy should focus on safety planning—not coercion.

🎭 Therapist Reflection: Am I respecting my client’s autonomy, or am I projecting urgency onto them?

Ethical Considerations When Working with Abusers

🚩 Therapists are ethically bound to prevent harm—but that doesn’t mean all abusers should be in therapy.

🔹 If an abuser is still harming their partner: Therapy should not be used as a band-aid or a confessional booth.

🔹 If they refuse accountability: Therapy may reinforce the idea that their emotions matter more than their actions.

🔹 If they want therapy as an alternative to legal consequences: Some abusers seek therapy to avoid consequences, not to change.

🔥 Pro tip: If an abuser is actively harming their partner, it is ethically responsible to refer them to a Batterer Intervention Program (BIP) rather than continue therapy.

🎭 Therapist Reflection: Am I providing therapy that actually prevents harm, or am I unintentionally reinforcing harmful behaviors?

Protecting Yourself as a Therapist

IPV cases can be high-risk for therapists, too—especially when working with abusive clients who become angry, threatening, or manipulative.

Signs You May Be at Risk as a Therapist:

🚩 The abusive partner calls or emails you, demanding details about their partner’s therapy.

🚩 You receive threats or intimidation attempts from the abusive partner.

🚩 The survivor reports that their abuser is tracking their appointments.

🚩 You notice stalking behaviors outside of session.

✅ Steps to Protect Yourself:

• NEVER disclose details to an abusive partner.

• Set firm boundaries around communication. (No discussing the survivor’s therapy under any circumstance.)

• Use professional discretion when documenting IPV cases. (Don’t write anything that could put the survivor at risk if their abuser gained access to records.)

• Consult with legal professionals if you feel your own safety is at risk.

🔥 Pro tip: Your safety matters too. If a case feels dangerous, seek support.

🎭 Therapist Reflection: Am I prioritizing my own safety and professional boundaries while working these cases?

🎭 Therapist Script: How to Communicate Ethical and Legal Boundaries to Clients

🔹 Client (Survivor): “If I tell you something, will you have to report it?”

🔹 Therapist: “I’ll always be honest with you about when I do or don’t have to break confidentiality. If you ever want to talk through that before sharing something, we can do that.”

🔹 Client (Abuser): “I want to do therapy instead of going to a program.”

🔹 Therapist: “Therapy and a structured intervention program serve different purposes. I can help you find a program that specializes in accountability-based change.”

🔹 Client (Survivor): “I don’t want you to report, but I also don’t feel safe.”

🔹 Therapist: “We can talk about what safety looks like for you and what resources are available—without pressure to report or take action you aren’t ready for.”

🔹 Client (Survivor): “My partner wants to call you to talk about therapy.”

🔹 Therapist: “I want to be really clear that I can’t and won’t share anything with them. Your therapy is for you, and my job is to protect that space.”

🔥 Pro tip: Transparency builds trust. Survivors need to know exactly where you stand before they share.

The Bottom Line

IPV therapy is high-stakes work. If therapists aren’t clear on their legal and ethical obligations, they risk causing harm, breaking trust, or putting clients in danger.

✅ Survivors need confidentiality, informed consent, and safety-focused therapy.

❌ Abusers should NOT be in therapy without clear accountability measures in place.

⚠️ Therapists must protect themselves legally and physically in high-risk cases.

When in doubt, consult, document wisely, and prioritize safety—both yours and the client’s.

The Responsibility (and Power) of Therapists in IPV Cases

If there’s one takeaway from this entire discussion, it’s this: Therapists hold immense power in IPV cases—and that power must be used responsibly.

We are often the first and sometimes the only people who see the full picture of what’s happening behind closed doors. We are the ones survivors cautiously test for safety. We are the ones abusers try to manipulate. And we are the ones who must decide whether our interventions will create real pathways to change or unintentionally reinforce harm.

There is no room for neutrality in IPV work. We either help break the cycle, or we allow it to continue.

The Core Commitments of Ethical IPV Therapy

At the heart of ethical IPV work is a simple truth: We do not treat relationships. We treat individuals.

✅ For survivors, therapy must prioritize:

• Safety, agency, and autonomy.

• Validation without pressure to leave.

• Practical tools for navigating risk and recovery.

✅ For abusers, therapy must be:

• Accountability-driven, not insight-driven.

• Focused on behavioral change, not emotional processing.

• Integrated with structured intervention programs.

🚨 Therapy should NEVER:

• Reinforce power imbalances by treating IPV as a “relationship issue.”

• Give abusers tools to manipulate more effectively.

• Push survivors toward actions they are not ready for.

🔥 Pro tip: When in doubt, return to this guiding question: “Is this intervention reducing harm, or is it making the abuse cycle easier to sustain?”

🎭 Therapist Reflection: Am I practicing therapy that actively disrupts the IPV cycle, or am I allowing therapy to become another tool for control?

Continuing Education & Consultation – Stay Sharp, Stay Ethical

IPV is one of the most complex clinical issues therapists face—and yet, many graduate programs barely scratch the surface.

If you’re going to work with IPV, commit to ongoing education and consultation.

🔹 Take IPV-specific training. Look for programs on trauma-informed therapy, Batterer Intervention Programs (BIPs), and legal/ethical considerations.

🔹 Join consultation groups. IPV work is emotionally demanding. Peer consultation helps prevent burnout and clinical missteps.

🔹 Know your local resources. Build relationships with domestic violence advocates, shelters, and legal aid organizations.

🔹 Challenge your own biases. IPV doesn’t always look how you expect it to—stay curious, stay humble.

🔥 Pro tip: IPV work is never done in isolation. Therapists who try to handle these cases alone risk missing red flags, overstepping ethical lines, or becoming emotionally drained.

🎭 Therapist Reflection: Am I committed to staying informed and accountable in my IPV work?

A Note on Therapist Boundaries & Emotional Sustainability

Therapists who work with IPV cases often carry secondary trauma, emotional exhaustion, and the weight of moral responsibility. It’s not unusual to feel:

🔹 Frustration when a survivor minimizes abuse or stays with their partner.

🔹 Anger toward abusers who manipulate the system.

🔹 Overwhelm from the ethical and legal complexities.

🔹 Fear for a client’s safety—sometimes even your own.

This is hard work. And you cannot pour from an empty cup.

✅ Protect yourself by: